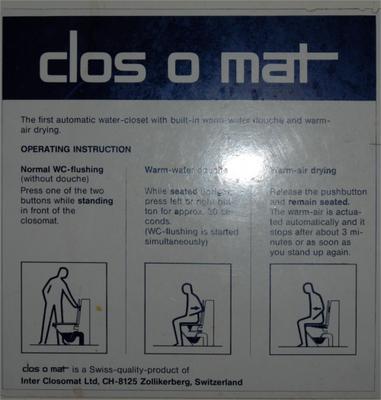

File this under "Random Things You Find In Africa." This gem is in the Diffa CARE office. How or when it got here is beyond me. I should see if I can order one for our place back in Madagascar.

Former Trailing Spouse's -- now back in the US and working in the DC Metro area -- musings on life.

I’ve spent a lot of time sitting behind computers and riding in cars these last three weeks. It’s hard for me to find inspiring and interesting material about computers, as nowadays this is SOP for most of us; and despite the wonders of the web and other technical advances, everything with computers is still a bunch of ones and zeros. You might think being a passenger in a car is as humdrum as working in front of a computer. But this is not so. Traversing the eastern reaches of Niger as a passenger has given me (ample) time to take in the scenery, catch up on sleep, and interact with the drivers. Eventually, however, the scenery stops being new and captivating, and you can only sleep so long before a pothole or an evasive maneuver—taken to avoid hitting some free ranging animal or child—wakes you. So, it’s only natural that your attention turns to your other human companions, which for me has been the driver du jour, assigned to schlep me from place to place. They're all top notch in my book and I've enjoyed my time with them, so I’d like share some vignettes that I’ve assembled. We all have our own quirks and habits that we do without thinking countless times in a day. And I know I’d hate having my quirks, no matter how innocent, funny or bizarre they might be, scrutinized and shared with strangers. With this in mind, I’ve changed the names to provide at least a thin veil of anonymity.

Adamou: Adamou drove me from Diffa to Maradi, a drive that lasted 10 hours. The drive is long, but Adamou made the drive even longer by stopping at almost every coffee and kola nut stand between Diffa and Maradi to get a fix. Add nicotine to the list of stimulants too, because each stop was an opportunity to smoke a cigarette. At one point he complained of a pounding behind his eyes and partial paralysis of his face. He reasoned that it was “L’Urgence” and the long hours causing the mysterious ailment. I think an equally plausible hypothesis is that he was hepped-up on too many stimulants and had some physiochemical imbalance going on.

A tall, slender man with a youthful face, Adamou wore, during the trek, no less than three different pairs of sunglasses (but never more than one pair at a time). He had sunglasses stashed on his person as well as in the car, and I could never learn what prompted a change from one pair to another. In talking with him, I discovered he was only 42 years old—I thought him to be much younger—and has had 12 children between his two wives. Six boys, six girls, two sets of twins. Gobsmacked doesn’t even come close to conveying my disbelief at his fecundity, and luck. I guess it's people like him who are keeping Niger's birthrate so high.

Moustapha: Moustapha was the first driver assigned to me at the start of my grand tour. The day before I left, the director sought me out and told me CARE Niamey has five drivers, four of whom are wonderful. And then there’s Moustapha. She assured me that he wasn’t dangerous, just hard to communicate with-in any language. Apparently the senior staff avoids taking trips with him, so he was really excited to learn that we were heading all the way to Diffa and would be away for at least two weeks. (He told me later, It’s good to travel; I can’t go for long periods being with my wife. I said, It must be the secret to your long and happy marriage. He agreed.)

During our first days together I saw why the director warned me. I know I’m not a fluent French speaker, and that I have a mélange of Malgache and Hausa in my head, so I’m accustomed to being not well understood; however, I can usually manage to get my point across when talking with someone. And nine times out of ten, I can communicate with Moustapha perfectly well, but that tenth time is a doozey. Usually our communication breakdown happens when giving or receiving directions. For example, I’d say, Moustapha, slow down; we’re coming up on our turn. He’d say, Turn here? Yeah, we’re going here, this is our turn; turn right here. Moustapha would say, Did you want me to turn back there? I’d reply, Yeah, you have to turn around; you missed it. Oh, you wanted me to turn right back there? Okay, violà, here we are. And so on.

It would be easy for me to conclude that he just doesn’t hear my French, but I’ve seen similar scenes played out between him and other Nigeriens. I felt better after learning this—that it’s not just me that struggles to communicate with him, and now I just laugh when we make a wrong turn, or when Moustapha starts some tangential conversation thread that only makes sense to him.

He also has a funny personal grooming habit that I can’t resist mentioning. We had just eaten lunch at Dogondutchi the first day out and were back on the road heading east. I was absorbed doing something and was startled to hear a hissing noise coming from our Land Cruiser. I thought the radiator had a problem, or that we’d blown a tire, but Moustapha’s face didn’t register any concern. In fact, he wore a wide smile as he stared ahead watching the road. Confused, I studied him for a few moments before two things dawned on me: 1) he wasn’t smiling; and 2) he was making the hissing noise with his mouth. With his lips pulled back, he was forcing air through his teeth to dislodge some morsel of food still caught in his teeth from lunch. Not finding success with his air-pressure method, he pulled down his sun visor to get out his dental hygiene heavy artillery: a Bic ballpoint pen. After discharging the stubborn bits, he replaced the cap to the pen and re-holstered it in the visor. I noticed he had more than one pen in the visor, but I have personally witnessed that when he’s picking, he’s not picky—he’ll use whatever “tool” is handy at the moment of crisis.

Inoussa: Speaking of picking, I have to mention Inoussa, who was my most recent driver, taking me from Konni to Tahoua. I had arrived in Konni early Saturday morning after taking the 4:30am bus from Maradi. I was waiting around the office in Konni when a heavy-laden Toyota pickup rolls in and out jumps Inoussa, a short, curly-haired Touareg man, sweating profusely. He informed me that he was to be my driver, but that he had to unload his truck and do some other errands before he’d be ready to leave. Fine, I said and went off to have a Nescafe with sweetened condensed milk, a concoction I’d normally gag over in the U.S., but a delicacy in Niger.

About an hour later Inoussa reappeared. We loaded up the truck and headed out of town. Like most of the CARE staff right now, he seemed fatigued: his eyes were two slits. He told me that the day before, he had made the drive between Konni and Tahoua four times. He was still sweating and asked me for some aspirin to help with a headache. I didn’t have any on me, so he stopped and bought some on the road just outside of Konni.

The drive to Tahoua is only a couple of hours long and that, combined with my napping, didn’t leave a lot of time to really connect with Inoussa. But the drive was sufficiently long for me to watch him engage in a truly perplexing habit. During a waking moment, I saw Inoussa remove a scrap piece of paper from the truck’s center console and tear off a strip about ½ inch wide and 3 inches long. Casually, but purposefully he then began to roll the strip of paper into a long, thin twist. He glanced at me sideways to see if I was watching—but with my mirrored sunglasses he wouldn’t be able to see my eyes—and then cautiously snaked the paper twist up into one of his nostrils. After a few exploratory pokes, he buried the twist into his nose and then erupted in a sneezing fit. He blew his nose into a handkerchief and then acted like nothing had happened. This happened one other time during the drive. It was truly fascinating to watch, I must admit. I could only think of three reasons for engaging in such behavior: to keep awake, purge his nostrils of boogers, or simply for pleasure.

Three drivers, three different personalities, all are good people who do a great job under difficult circumstances. I used to think that I’d like to be a driver for a NGO: you get to drive nice cars, you receive per diem when you’re out on mission, and there’s a certain status that drivers possess. But now, knowing that I might come under such close scrutiny, I think I might have to rethink my dream job.

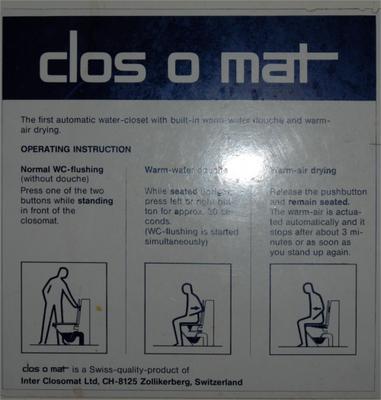

This is going to be a tough clean up.

This is going to be a tough clean up.

I’ve been out in the field since last Saturday visiting the regional offices where CARE is distributing food rations to villages. At this time, CARE’s response to the food crisis is limited to the regions of Tahoua, Maradi, Zinder, and Diffa. In Tahoua, Maradi, and Diffa they are distributing food rations supplied by World Food Program and Niger’s government. In addition to the distribution, in Tahoua and Zinder CARE is opening feeding stations in select villages to aid moderately malnourished children. There are other NGOs who are also distributing food rations, but in terms of scale of operation and the number of people served, CARE’s operation is among the largest. They might have an advantage over other NGOs because they have been working in Niger for such a long time and already have a lot of resources on the ground and built up capacity in their staff. Also, being a large NGO with a worldwide presence, they can call upon experts from other field offices to help. I’ve met CARE employees and contractors on loan from CARE USA, CARE Germany, CARE France, and CARE Haiti.

So far, my primary role has been getting CARE’s field reporting operational. I’ve spent most of my time in front of a computer working with the various forms and reports that CARE is obligated to produce to satisfy the donors who are helping fund its operations, as well as to document and evaluate its actions during this period. Not very sexy, but I feel like I’m playing an important role. (Kristen wrote in an email that she was glad I’m doing important work; she would be pissed if I was just running the XEROX machine.) I have another week or so to go in this tour of field offices before I head back to Niamey. Once all the reporting tools are finalized, I’m looking forward to my secondary role: writing qualitative narratives, collected from the field, about the beneficiaries touched by CARE.

I've stolen some time to get this posted and now I have to relinquish the precious VSAT connection for some real work, so I'll sign off now. I'll try to post more soon.