Saturday, November 05, 2005

Taxi rides in Tana

Taxi rides in Tana are, more often than not, an adventure. Tana (the thankfully shortened moniker for Antananarivo – “The City of a Thousand”, Madagascar’s capital) is a hilly city. Think: San Francisco, without bay views (or earthquakes). After their conquest of the city in 1895, the French invested no small amount of money in the capital in their effort to turn it into a city akin to what one might find in southern France. I’m not sure that they were successful. Furthermore, I doubt that the cobblestone streets in the Old Town have been replaced since 1895, which contribute to the reckless abandon with which taxi drivers hasten to navigate their 1960 era Peugots (full of holes themselves) around the gaps of missing cobblestones and bumps of upended cobblestones. Descending from the Old Town, the streets become paved, enabling the taxis to augment their speed, but the passages remain narrow and curvy, causing passengers to reach for oh shit handles which don’t exist. As one enters the sprawling ‘suburbs’, the streets become roads more recognizable to those of us who grew up in places with well-run Departments of Transportation: lines separating the lanes, designated turn lanes, and roundabouts labeled with clear signs. Despite this sense of order, taxi drivers don’t feel obliged to remain in their lanes, crossing over into the oncoming traffic lane at will to pass slower vehicles (paying no heed to looming oncoming traffic).

In Fianar, my daily commute to work is a four minute walk. Commutes in Tana are a stark contrast, and when I visit Tana, my morning routine becomes a race against the clock when I suddenly remember at 7:00 that I need to allow at least 30 to 60 minutes for the commute to get to my first meeting. Traffic jams seem worse than those in the US, as catalytic converters and environmental air pollution laws are unknown in Madagascar; numerous vehicles spew trails of dark smoke.

Two weeks ago when I was in Tana, I had an especially fun taxi ride. I had an appointment downtown at 2:30, and as I was staying in the burbs with an expatriate friend, I left the house to walk up to the main road to catch a taxi around 1:30. It was Saturday, so I hoped there wouldn’t be too much traffic. I am at the point in Malagasy where I can hail a taxi and tell the driver where I need to go (and that’s about it). I don’t know what I said, but the taxi man thought that I spoke fluent Malagasy. He proceeded to converse with me throughout the ride. Every few minutes, I’d recognize a smidgen of what he was talking about, enough to throw in an appropriate word, and he kept on chatting. He wasn’t convinced of my lack of language skills, even when I would say things in French and explained that I really don’t speak Malagasy.

One feature of taxi rides in Tana is coasting. It’s an art form, really. As we pulled out, I felt like we were going a little too fast – till I realized it was because we were approaching a hill down which the driver intended to coast at top speed. We picked up enough momentum that we were able to pass another taxi as we barreled down the hill. One disconcerting feature of this taxi was that the driver had to wrench the steering wheel to the left immediately before shifting. We stopped at a gas station along the way, and he grabbed a 1 liter plastic water bottle out of the front seat, and filled it with gas. I assumed he would then fill up some other plastic container under the hood– proper gas tanks aren’t deemed a necessity for taxis around here – instead, he replaced the bottle full of fuel on a shelf under the glove compartment, carefully positioning it so it wouldn’t spill, and we drove the rest of the way with our extra gasoline inside the car.

I tend not to favor unsafe conditions which are out of my control, and more often than not taxi rides in Tana certainly fall into that category. For some reason, though, these taxi rides almost always put me in a pleasant mood. The unexpected moments bring a smile, and make up for the long commute.

Wednesday, November 02, 2005

Parting thoughts on Diffa

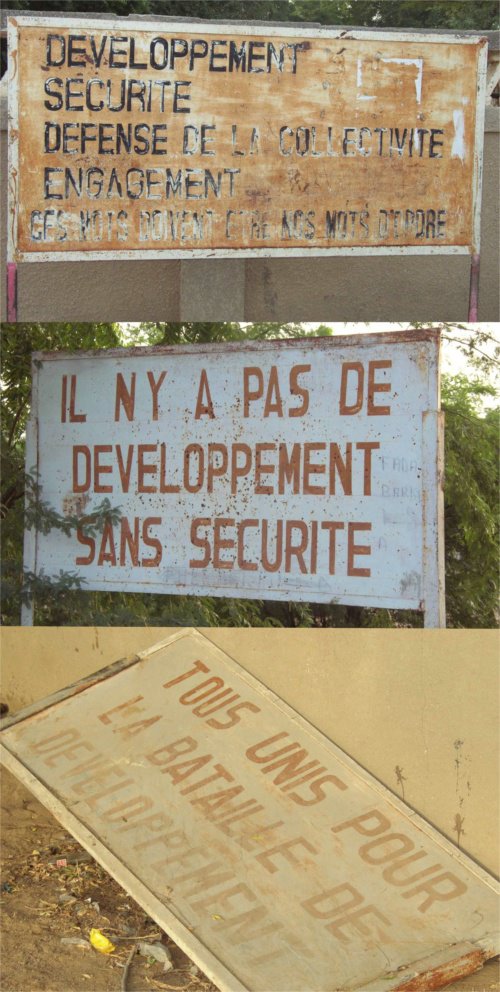

Kountché era slogans

Today I saw a goat wearing a tomato paste can as a shoe. Except for some difficulty traversing the road, he seemed untroubled by his new footwear. Niger never stops delighting my sense of humor.

The big news is that the month of Ramadan officially ended yesterday. Every year brings a huge debate over the starting and ending dates of the month, because some locales claim to see the moon earlier or later than others. Last night there was added tension in Diffa where an unusual cloudy evening obscured all celestial bodies, making the radio and television the go-to source for confirming the month’s end. I woke up this morning at my usual time, asked the guardian if today was the fête, he said yes, so I went back to sleep until 11. I think I’ve had some pent up exhaustion from the past two months and was grateful for the rest. Walking to the office, even at the noon hour, there were gangs of people in the street dressed in new outfits and making merry, clearly very happy that another year of Ramadan has ended.

The houseflies in Diffa have started taking a greater interest in my morning commutes lately. At first I wondered if I had neglected some crucial step in my morning personal hygiene routine. A mental audit, however, came back negative on that front and a quick sniff of the pits confirmed that I didn’t carry the scent of carrion on my person. I’ve concluded that the hitchhiking flies were a harbinger of the approaching cold season. This assessment seemed strengthened by the presence of dust-filled skies, another horseman of the harmmatan. Only the mornings are hazy, the sun still has enough strength to burn through the dust to make daytime temperatures sufficiently hot and miserable. Soon, the wind will suspend enough dust—and black plastic bags—to render the sky a reasonable proxy of a nuclear winter. The lower temperatures will provoke complaints from the average Abdou, and second-hand ski parkas will become this season’s “must have” fashion item. But, by the time this happens I will have left Diffa, and its houseflies, behind.

I feel a bit conflicted about leaving Diffa. I didn’t anticipate spending as much time in this corner of Niger as I have, and it’s been a mixed bag. The hardest part has been dietary. There are few restaurants here, and during Ramadan the only restaurant I had found stopped serving food halfway through the month. I’ve lived off corn flakes, sardines and fried bean cakes for the past three weeks. I only had one cartoon-like moment where a person talking to me stopped being a person and was transformed into a giant talking piece of fruit. All in all, that seems pretty good to me.

What I’ve found is that Diffa seems largely anachronistic. If Mark Twain had lived in Niger, he might have chosen Diffa as the place to live should the world have ended instead of Kentucky. I can imagine that this unchanging characteristic is a source of comfort for some and discomfort for others, particularly the youth. Aside from the presence of cell phones and a zillion motorcycles, I don’t imagine that Diffa has substantially changed in twenty years. It is the only place I’ve been in Niger that still has Kountché-era billboards on display, which are largely propagandistic and military in tone. In essence, they all portray “development” as a fight that can only be won with a secure state and a cooperative (i.e., compliant) populace. What was true then for Diffa, I think, is still true today. Being so remote, Diffa has cultivated a strong sense of independence and is viewed cautiously from Niamey as a place with the potential to incubate political unrest.

Upon entering Diffa from the west, you pass under an archway with a statue of solider on horseback atop the arch. Local lore has it that if you look at the horse as you are leaving town then you will return to Diffa another day. People at the office have been teasing me that each time I leave Diffa I look at the horse and that’s what keeps bringing me back. This time I’m not taking any chances—I’m going to be blindfolded. Maybe I’m not as conflicted as I think.

Tuesday, November 01, 2005

Kristen explains her fellowship

The four stars stand for: Nature, Health, Wealth, and Power

Kristen serves as a population, health, and environment advisor for SantéNet, a USAID funded comprehensive health project, in their Fianarantsoa regional office. Kristen has participated actively in the conceptualization and launch of Kominina Mendrika (Champion Commune), a commune level mobilization and demand creation approach to achieve health, environment, economic development, and good governance goals.

She is charged with contributing to the organizational development of three Malagasy NGOs which are implementing partners for Kominina Mendrika (KM). The NGOs are members of Voahary Salama, a Malagasy association dedicated to integrating health, population, and environment. Kristen collaborated with the Ecoregional Initiatives (ERI) project and the NGOs to develop complementary environment activities (funded by ERI) in six communes where the NGOs are concurrently implementing the health component of KM (funded by SantéNet).

Kristen is coalescing partners for water, sanitation, and hygiene initiatives in the Ranomafana – Andringitra forest corridor. She will also document a history of PHE initiatives in Fianarantsoa from 1990 to the present.