Saturday, November 05, 2005

Taxi rides in Tana

Taxi rides in Tana are, more often than not, an adventure. Tana (the thankfully shortened moniker for Antananarivo – “The City of a Thousand”, Madagascar’s capital) is a hilly city. Think: San Francisco, without bay views (or earthquakes). After their conquest of the city in 1895, the French invested no small amount of money in the capital in their effort to turn it into a city akin to what one might find in southern France. I’m not sure that they were successful. Furthermore, I doubt that the cobblestone streets in the Old Town have been replaced since 1895, which contribute to the reckless abandon with which taxi drivers hasten to navigate their 1960 era Peugots (full of holes themselves) around the gaps of missing cobblestones and bumps of upended cobblestones. Descending from the Old Town, the streets become paved, enabling the taxis to augment their speed, but the passages remain narrow and curvy, causing passengers to reach for oh shit handles which don’t exist. As one enters the sprawling ‘suburbs’, the streets become roads more recognizable to those of us who grew up in places with well-run Departments of Transportation: lines separating the lanes, designated turn lanes, and roundabouts labeled with clear signs. Despite this sense of order, taxi drivers don’t feel obliged to remain in their lanes, crossing over into the oncoming traffic lane at will to pass slower vehicles (paying no heed to looming oncoming traffic).

In Fianar, my daily commute to work is a four minute walk. Commutes in Tana are a stark contrast, and when I visit Tana, my morning routine becomes a race against the clock when I suddenly remember at 7:00 that I need to allow at least 30 to 60 minutes for the commute to get to my first meeting. Traffic jams seem worse than those in the US, as catalytic converters and environmental air pollution laws are unknown in Madagascar; numerous vehicles spew trails of dark smoke.

Two weeks ago when I was in Tana, I had an especially fun taxi ride. I had an appointment downtown at 2:30, and as I was staying in the burbs with an expatriate friend, I left the house to walk up to the main road to catch a taxi around 1:30. It was Saturday, so I hoped there wouldn’t be too much traffic. I am at the point in Malagasy where I can hail a taxi and tell the driver where I need to go (and that’s about it). I don’t know what I said, but the taxi man thought that I spoke fluent Malagasy. He proceeded to converse with me throughout the ride. Every few minutes, I’d recognize a smidgen of what he was talking about, enough to throw in an appropriate word, and he kept on chatting. He wasn’t convinced of my lack of language skills, even when I would say things in French and explained that I really don’t speak Malagasy.

One feature of taxi rides in Tana is coasting. It’s an art form, really. As we pulled out, I felt like we were going a little too fast – till I realized it was because we were approaching a hill down which the driver intended to coast at top speed. We picked up enough momentum that we were able to pass another taxi as we barreled down the hill. One disconcerting feature of this taxi was that the driver had to wrench the steering wheel to the left immediately before shifting. We stopped at a gas station along the way, and he grabbed a 1 liter plastic water bottle out of the front seat, and filled it with gas. I assumed he would then fill up some other plastic container under the hood– proper gas tanks aren’t deemed a necessity for taxis around here – instead, he replaced the bottle full of fuel on a shelf under the glove compartment, carefully positioning it so it wouldn’t spill, and we drove the rest of the way with our extra gasoline inside the car.

I tend not to favor unsafe conditions which are out of my control, and more often than not taxi rides in Tana certainly fall into that category. For some reason, though, these taxi rides almost always put me in a pleasant mood. The unexpected moments bring a smile, and make up for the long commute.

Wednesday, November 02, 2005

Parting thoughts on Diffa

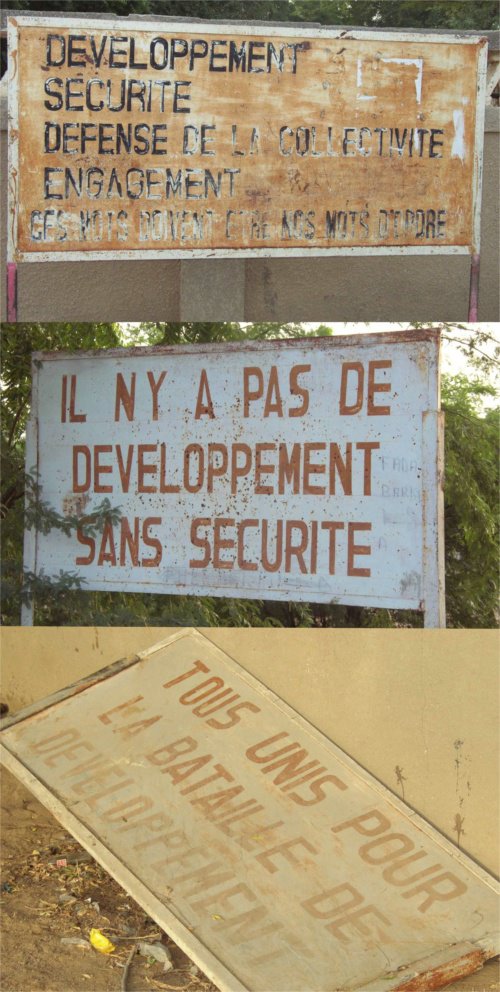

Kountché era slogans

Today I saw a goat wearing a tomato paste can as a shoe. Except for some difficulty traversing the road, he seemed untroubled by his new footwear. Niger never stops delighting my sense of humor.

The big news is that the month of Ramadan officially ended yesterday. Every year brings a huge debate over the starting and ending dates of the month, because some locales claim to see the moon earlier or later than others. Last night there was added tension in Diffa where an unusual cloudy evening obscured all celestial bodies, making the radio and television the go-to source for confirming the month’s end. I woke up this morning at my usual time, asked the guardian if today was the fête, he said yes, so I went back to sleep until 11. I think I’ve had some pent up exhaustion from the past two months and was grateful for the rest. Walking to the office, even at the noon hour, there were gangs of people in the street dressed in new outfits and making merry, clearly very happy that another year of Ramadan has ended.

The houseflies in Diffa have started taking a greater interest in my morning commutes lately. At first I wondered if I had neglected some crucial step in my morning personal hygiene routine. A mental audit, however, came back negative on that front and a quick sniff of the pits confirmed that I didn’t carry the scent of carrion on my person. I’ve concluded that the hitchhiking flies were a harbinger of the approaching cold season. This assessment seemed strengthened by the presence of dust-filled skies, another horseman of the harmmatan. Only the mornings are hazy, the sun still has enough strength to burn through the dust to make daytime temperatures sufficiently hot and miserable. Soon, the wind will suspend enough dust—and black plastic bags—to render the sky a reasonable proxy of a nuclear winter. The lower temperatures will provoke complaints from the average Abdou, and second-hand ski parkas will become this season’s “must have” fashion item. But, by the time this happens I will have left Diffa, and its houseflies, behind.

I feel a bit conflicted about leaving Diffa. I didn’t anticipate spending as much time in this corner of Niger as I have, and it’s been a mixed bag. The hardest part has been dietary. There are few restaurants here, and during Ramadan the only restaurant I had found stopped serving food halfway through the month. I’ve lived off corn flakes, sardines and fried bean cakes for the past three weeks. I only had one cartoon-like moment where a person talking to me stopped being a person and was transformed into a giant talking piece of fruit. All in all, that seems pretty good to me.

What I’ve found is that Diffa seems largely anachronistic. If Mark Twain had lived in Niger, he might have chosen Diffa as the place to live should the world have ended instead of Kentucky. I can imagine that this unchanging characteristic is a source of comfort for some and discomfort for others, particularly the youth. Aside from the presence of cell phones and a zillion motorcycles, I don’t imagine that Diffa has substantially changed in twenty years. It is the only place I’ve been in Niger that still has Kountché-era billboards on display, which are largely propagandistic and military in tone. In essence, they all portray “development” as a fight that can only be won with a secure state and a cooperative (i.e., compliant) populace. What was true then for Diffa, I think, is still true today. Being so remote, Diffa has cultivated a strong sense of independence and is viewed cautiously from Niamey as a place with the potential to incubate political unrest.

Upon entering Diffa from the west, you pass under an archway with a statue of solider on horseback atop the arch. Local lore has it that if you look at the horse as you are leaving town then you will return to Diffa another day. People at the office have been teasing me that each time I leave Diffa I look at the horse and that’s what keeps bringing me back. This time I’m not taking any chances—I’m going to be blindfolded. Maybe I’m not as conflicted as I think.

Tuesday, November 01, 2005

Kristen explains her fellowship

The four stars stand for: Nature, Health, Wealth, and Power

Kristen serves as a population, health, and environment advisor for SantéNet, a USAID funded comprehensive health project, in their Fianarantsoa regional office. Kristen has participated actively in the conceptualization and launch of Kominina Mendrika (Champion Commune), a commune level mobilization and demand creation approach to achieve health, environment, economic development, and good governance goals.

She is charged with contributing to the organizational development of three Malagasy NGOs which are implementing partners for Kominina Mendrika (KM). The NGOs are members of Voahary Salama, a Malagasy association dedicated to integrating health, population, and environment. Kristen collaborated with the Ecoregional Initiatives (ERI) project and the NGOs to develop complementary environment activities (funded by ERI) in six communes where the NGOs are concurrently implementing the health component of KM (funded by SantéNet).

Kristen is coalescing partners for water, sanitation, and hygiene initiatives in the Ranomafana – Andringitra forest corridor. She will also document a history of PHE initiatives in Fianarantsoa from 1990 to the present.

Sunday, October 30, 2005

Cereal Treats

After spending two years in Niger during the Peace Corps I am accustomed to finding rocks in my food. If you want to avoid visiting a Nigerien dentist, it doesn’t take long for you to develop a “soft mouth” (to borrow a hunting concept) when approaching a potential meal. You also unconsciously begin classifying food into three groups with regard to rock content: definitely has some, might have some, does not have any. Finding “rocks” in my corn flakes—generally a might-have-some product—this morning, however, is just about beyond my limit. I guess the NASCO cereal plant in Nigeria has a few kinks in its processing system that is responsible for producing these corn nuggets.

It reminds me a little of what a friend once said after finding hairs (note, plural) in a meal at a restaurant—One hair is an accident; more than that, an ingredient.

Saturday, October 29, 2005

Eaststate Office Boyz

Hangin’ with ma comptrolla boyz

This is my Diffa crew, Karouna (l) and Ali (r). At some point I realized I had become a humanitarian bean counter, tracking down the whereabouts and details of the food distribution, and felt that I had become a little like my favorite guest columnist at The Onion, Herbert Kornfeld. Word is bond.

Thursday, October 20, 2005

A Food Distribution in Bosso

Like many places in Niger, the road to Bosso is not an easy one. Located 100 kilometers east of Diffa, the last sixty kilometers is off the main paved road and is a maze of braided tire tracks that crisscross over what was once, in ancient times, the lakebed of Lake Chad. The water from Lake Chad has long since retreated and what is left is just a vast expanse of flat, open space.

An abundance of Acacia trees and short species of golden grasses fill this openness and explain why this area is classified a pastoral zone. Rain-fed agriculture in this region is small in scale, and largely folly. Yet, so attached to millet is the Nigerien psyche, farmers still continue to plant small fields to the crop, hoping to have an above-average year of precipitation. Such gambles rarely pay out, and most households end up buying millet (or other cereals) from the market. Playing to this area’s strengths, most people here earn at least some portion of their living from livestock, which is ubiquitous.

A hardscrabble existence is the norm for most Nigeriens. Subsistence farming—a mix of agriculture and animal husbandry—is what most people do for a living. But, an increasing population and decreasing soil productivity threaten this way of life. Climate also plays a role where inadequate and poorly distributed rainfall routinely threaten harvests throughout the country, and some places—notably in the regions of Maradi, Zinder, and Diffa—face severe food shortages and drought every year. And, even in years when the rains are good and crop yields are average, a recent report showed that the most vulnerable—read poorest—households are only able to grow enough food to meet their cereal needs for just six months out of a year.

Last year, poor rains and a locust invasion left both crops and pasture in poor shape and, as a result, rendered many households vulnerable to food shortages. After last year’s disappointing harvest, estimates from the government came out showing that 2.7 million people, in 4000 communities—one-quarter of Niger’s total population—would be affected by a food shortage in coming year. Bosso, and several of the surrounding villages, were identified as being vulnerable, and were selected to receive food aid from the World Food Programme (WFP). CARE took responsibility for distributions in this region and dispatched teams to Bosso and the other villages in early October to await the delivery of rations from the WFP.

So, it was on a recent Friday morning in Bosso that the town criers began circulating at 3:30 am, their shouts and drumming rousing the villagers and CARE distribution team from sleep. During Ramadan, the holy month of fasting for Muslims, the criers—whose job it is to wake people to remind them to eat and drink before the sun rises and another day of thirst and hunger begins—make owning an alarm clock pointless. Once awake, the team members sluggishly left their mosquito nets, ate their morning meal, exchanged a few quiet words among themselves, and then slipped back into their beds to get a couple more hours of sleep before a long day of food distributions was set to begin.

Later, after the sun was above the horizon, the team woke up for a second time and walked down to the warehouse where the WFP food rations were stored and where they would set up a staging area for the actual distribution. An unexpected surprise awaited the team at the warehouse: four WFP trucks, filled with sacs of maize and beans, had arrived during the night and were waiting to be unloaded. Once offloaded, this food would be sent to nearby distribution centers, where other CARE teams would be waiting for the arrival of these rations to begin their own distributions.

Thursday, the day before, the team had visited the villages of Yebi and Boulountoungou to inform the residents that their time to receive food had arrived and to show up at Bosso the next morning. Now, only 7:30 am, villagers were already arriving and staking claim to the few shady sitting spots; as is the norm, men and women sat separately under different trees. And, every thirty minutes or so, those sitting at the shade’s edge would silently rise and move deeper into the shade, like human sundials.

Everyone was patient, but visibly eager, as the distribution team readied themselves. Strong men, drenched in sweat, hauled 50 kg sacs of beans and maize from the warehouse and made neat stacks near the entrance: five for beans, ten for maize. Small children, filled with curiosity and mischief couldn’t resist climbing on the stacks. An adult noticed the horseplay and shooed them away. Quickly forgotten, the kids, masters of stealth, resumed their game until the next reprimand. This drama between the kids and adults replayed again and again until the distributions finally started.

Yaka, a young Kanouri woman from Boulountoungou, sat under a large shade tree with the other women waiting for her name to be called so she could collect her family’s food ration. Like many Nigeriens, she planted millet during the rainy season, but the yield, she said, would only last two months. Still, compared to some of her neighbors, she considers herself fortunate. Even so, she is thankful that the Niger government, WFP and CARE have intervened during this year of hunger. A single mother with six children in her charge, Yaka was eager to receive the 100 kg of maize and 15 kg of beans allotted to her. With the rations, she said that in a day she would prepare two tias (a local measure, weighing approximately 2 kilograms) of maize and one of beans. If she sticks to this plan, the beans will last a week; the maize, 5 weeks. She tries, with difficulty, to think beyond these 5 weeks and wonders what she will do once her allotment runs out.

The queue of people moved slowly through the distribution station. Each person waited in line holding a numbered piece of paper. In addition to the number were notes on each slip indicating the size of ration each person was to receive. First, a CARE team member verified the identity of each person and made an impression of their fingerprint. Next, another team member read on the numbered piece of paper how many tias of beans to issue. Then, one of the strong men carried out the appropriate number of sacs of maize. And so it went with the next person in line. The process was incredibly slow, but despite the wait (and the heat), people were patient.

By mid-day, the team finished distributing food to the Yebi residents. The team looked hot and tired, and ready for a well-deserved rest. Meanwhile, under a blistering sun, people labeled their sacs of maize and made arrangements for transport back to Yebi. Some had come with donkeys or camels to bring back the rations. Others paid 200 naira (US$1.40) apiece to have their allotment transported by a vintage Toyota Land Cruiser pickup. Two men loaded their sacs onto motorcycles, lashed them down with rope, and then rode off looking dangerously unstable. And a few others carried small bags of beans atop their heads and struck off on foot.

Yaka, and the others from Boulountoungou, waited until the afternoon to receive their rations. The distribution process was identical to that of the morning, and finally, the team called her number. After she had collected her share, she watched as it was loaded into the back of a hired truck that would deliver the food to the village. It had been a long day, and it would be dark by the time she returned home. Despite the late hour, she probably prepared some of the food. It would have been a long time since she could eat until she was full, and the call of the criers always comes too soon during Ramadan.

Yaka’s story is not unusual for Niger; there are families like hers all across the country. It is almost certain, given the environmental, climatic, and demographic risk factors, that Niger will again face more food shortages in the future. Less certain is if these shortages will be localized or more extensive, affecting a greater proportion of the population. At least now, thanks to the food provided by WFP and distributed by CARE, Yaka, and households like hers, will have one less thing to worry about, even if it is for just 5 weeks.

Wednesday, October 12, 2005

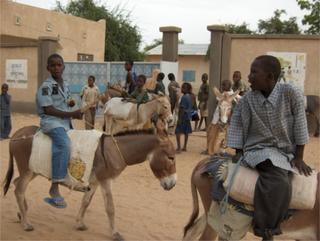

Donkey Boys of Diffa

Since August CARE Niger has been in the middle of a whirlwind of activity distributing food aid from the WFP to hungry communities in the regions of Tahoua, Maradi and Diffa. The scale of the operation is enormous and has consumed nearly all of the resources, time and energy of CARE’s dedicated workforce. The hard work and sacrifice will have been worth the result: by the end of the operation, set for October 10, CARE will have distributed over 16,000 tons of food to 900,000 people in Niger. In a place where just-in-time delivery is still a fantasy, this accomplishment—in only 8 weeks—is nothing short of miraculous.

That the food even made it to the communities is equally miraculous. A sac of maize grown in Iowa and consumed in N’Guigmi, Niger has come a long way. And nearly every imaginable mode of transportation has been used to move the sac along its journey. But there is one mode of transportation that stands out from the others as unique and noteworthy. When the trucks discharge their food in the communities, the most critical distance—from distribution point to household—is often serviced by the poor man’s SUV, the lowly donkey.

In Niger you cannot talk of donkeys and not mention the young boys that tend them, for they go hand in hand. What can you say about a boy and his donkey? I won’t suggest that the bond is on par with that seen between Timmy and Lassie, but there is something special there. And, years from now, 2005 will likely stand out in the minds of many Nigerien boys as the year that CARE International brought their community food, and as the year they made bank—thanks to their trusty steed.

The distributions have had an unintended—and positive—economic impact in the small and often neglected demographic of prepubescent entrepreneur. If, at each stage of transportation, someone has received payment for rendered services associated with the food rations, why should the donkey boys be any different?

What kind of economic impact has the donkey transport business had in Niger? Let’s do some hypothesizing using Diffa as an example. In Diffa, the going rate for transporting a 50 kg bag of cereal is 40 Naira (approximately 30 cents). CARE will distribute 3,000 tons of cereal in this region. If donkeys deliver 1,000 tons (20,000 sacs) from distribution center to household, they would generate an income of US $6,000 for their owners. In a place where the GNP is only US $170, this is serious cash.

In the process, not only do these boys earn some pocket money, they also learn some important business lessons. First-mover advantage is applicable here. Those boys who showed up first with their donkeys had a captive market and could reap the lion’s share of any profits. But they then learned that first-mover advantage dissipates quickly in the face of competition. They learn about barriers to entry, which, for donkey transport, are fairly low: If you have a donkey, you can play. And, when distributions finally come to an end, they will need to learn the cruel lesson of what happens when supply outstrips demand.

The donkey also gets an education in economics from this experience. It learns that if trickle down economics can’t work in the United States that it won’t work in Niger either. For all its hard work, the donkey probably didn’t receive any improved rations. Even Lassie would have earned a choice bone if she had earned Timmy a quick 20 bucks.

Tuesday, October 04, 2005

Nigerian Truck Art

Why 56 km/h?

I saw this truck in N’Guigmi last week and couldn't resist taking its picture. Truck art is fairly common here and Nigeria, the port of call for this truck, produces some top-notch painters in this genre. It’s surely symbolic on some level, but the meanings are lost on me.

Forget the unlikelihood of ever seeing a scene such as this acted out in nature and take in the aesthetics. Appreciate the artist’s use of colors. Marvel at the level of detail, like the rivulets of blood coming from the crocodile’s leg and head, where the lion has dug in its claws and teeth. And, while I can understand the artist’s desire to be anatomically correct, did he really need to add scrotums to the lion and ram? Come on, doesn't it seem a bit unnecessary?

Friday, September 30, 2005

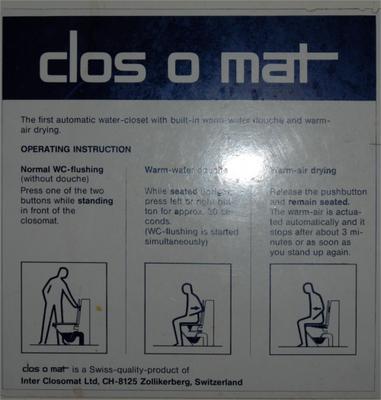

The CLOS-O-MAT

File this under "Random Things You Find In Africa." This gem is in the Diffa CARE office. How or when it got here is beyond me. I should see if I can order one for our place back in Madagascar.

Friday, September 23, 2005

Driving Mr. Dan

I’ve spent a lot of time sitting behind computers and riding in cars these last three weeks. It’s hard for me to find inspiring and interesting material about computers, as nowadays this is SOP for most of us; and despite the wonders of the web and other technical advances, everything with computers is still a bunch of ones and zeros. You might think being a passenger in a car is as humdrum as working in front of a computer. But this is not so. Traversing the eastern reaches of Niger as a passenger has given me (ample) time to take in the scenery, catch up on sleep, and interact with the drivers. Eventually, however, the scenery stops being new and captivating, and you can only sleep so long before a pothole or an evasive maneuver—taken to avoid hitting some free ranging animal or child—wakes you. So, it’s only natural that your attention turns to your other human companions, which for me has been the driver du jour, assigned to schlep me from place to place. They're all top notch in my book and I've enjoyed my time with them, so I’d like share some vignettes that I’ve assembled. We all have our own quirks and habits that we do without thinking countless times in a day. And I know I’d hate having my quirks, no matter how innocent, funny or bizarre they might be, scrutinized and shared with strangers. With this in mind, I’ve changed the names to provide at least a thin veil of anonymity.

Adamou: Adamou drove me from Diffa to Maradi, a drive that lasted 10 hours. The drive is long, but Adamou made the drive even longer by stopping at almost every coffee and kola nut stand between Diffa and Maradi to get a fix. Add nicotine to the list of stimulants too, because each stop was an opportunity to smoke a cigarette. At one point he complained of a pounding behind his eyes and partial paralysis of his face. He reasoned that it was “L’Urgence” and the long hours causing the mysterious ailment. I think an equally plausible hypothesis is that he was hepped-up on too many stimulants and had some physiochemical imbalance going on.

A tall, slender man with a youthful face, Adamou wore, during the trek, no less than three different pairs of sunglasses (but never more than one pair at a time). He had sunglasses stashed on his person as well as in the car, and I could never learn what prompted a change from one pair to another. In talking with him, I discovered he was only 42 years old—I thought him to be much younger—and has had 12 children between his two wives. Six boys, six girls, two sets of twins. Gobsmacked doesn’t even come close to conveying my disbelief at his fecundity, and luck. I guess it's people like him who are keeping Niger's birthrate so high.

Moustapha: Moustapha was the first driver assigned to me at the start of my grand tour. The day before I left, the director sought me out and told me CARE Niamey has five drivers, four of whom are wonderful. And then there’s Moustapha. She assured me that he wasn’t dangerous, just hard to communicate with-in any language. Apparently the senior staff avoids taking trips with him, so he was really excited to learn that we were heading all the way to Diffa and would be away for at least two weeks. (He told me later, It’s good to travel; I can’t go for long periods being with my wife. I said, It must be the secret to your long and happy marriage. He agreed.)

During our first days together I saw why the director warned me. I know I’m not a fluent French speaker, and that I have a mélange of Malgache and Hausa in my head, so I’m accustomed to being not well understood; however, I can usually manage to get my point across when talking with someone. And nine times out of ten, I can communicate with Moustapha perfectly well, but that tenth time is a doozey. Usually our communication breakdown happens when giving or receiving directions. For example, I’d say, Moustapha, slow down; we’re coming up on our turn. He’d say, Turn here? Yeah, we’re going here, this is our turn; turn right here. Moustapha would say, Did you want me to turn back there? I’d reply, Yeah, you have to turn around; you missed it. Oh, you wanted me to turn right back there? Okay, violà, here we are. And so on.

It would be easy for me to conclude that he just doesn’t hear my French, but I’ve seen similar scenes played out between him and other Nigeriens. I felt better after learning this—that it’s not just me that struggles to communicate with him, and now I just laugh when we make a wrong turn, or when Moustapha starts some tangential conversation thread that only makes sense to him.

He also has a funny personal grooming habit that I can’t resist mentioning. We had just eaten lunch at Dogondutchi the first day out and were back on the road heading east. I was absorbed doing something and was startled to hear a hissing noise coming from our Land Cruiser. I thought the radiator had a problem, or that we’d blown a tire, but Moustapha’s face didn’t register any concern. In fact, he wore a wide smile as he stared ahead watching the road. Confused, I studied him for a few moments before two things dawned on me: 1) he wasn’t smiling; and 2) he was making the hissing noise with his mouth. With his lips pulled back, he was forcing air through his teeth to dislodge some morsel of food still caught in his teeth from lunch. Not finding success with his air-pressure method, he pulled down his sun visor to get out his dental hygiene heavy artillery: a Bic ballpoint pen. After discharging the stubborn bits, he replaced the cap to the pen and re-holstered it in the visor. I noticed he had more than one pen in the visor, but I have personally witnessed that when he’s picking, he’s not picky—he’ll use whatever “tool” is handy at the moment of crisis.

Inoussa: Speaking of picking, I have to mention Inoussa, who was my most recent driver, taking me from Konni to Tahoua. I had arrived in Konni early Saturday morning after taking the 4:30am bus from Maradi. I was waiting around the office in Konni when a heavy-laden Toyota pickup rolls in and out jumps Inoussa, a short, curly-haired Touareg man, sweating profusely. He informed me that he was to be my driver, but that he had to unload his truck and do some other errands before he’d be ready to leave. Fine, I said and went off to have a Nescafe with sweetened condensed milk, a concoction I’d normally gag over in the U.S., but a delicacy in Niger.

About an hour later Inoussa reappeared. We loaded up the truck and headed out of town. Like most of the CARE staff right now, he seemed fatigued: his eyes were two slits. He told me that the day before, he had made the drive between Konni and Tahoua four times. He was still sweating and asked me for some aspirin to help with a headache. I didn’t have any on me, so he stopped and bought some on the road just outside of Konni.

The drive to Tahoua is only a couple of hours long and that, combined with my napping, didn’t leave a lot of time to really connect with Inoussa. But the drive was sufficiently long for me to watch him engage in a truly perplexing habit. During a waking moment, I saw Inoussa remove a scrap piece of paper from the truck’s center console and tear off a strip about ½ inch wide and 3 inches long. Casually, but purposefully he then began to roll the strip of paper into a long, thin twist. He glanced at me sideways to see if I was watching—but with my mirrored sunglasses he wouldn’t be able to see my eyes—and then cautiously snaked the paper twist up into one of his nostrils. After a few exploratory pokes, he buried the twist into his nose and then erupted in a sneezing fit. He blew his nose into a handkerchief and then acted like nothing had happened. This happened one other time during the drive. It was truly fascinating to watch, I must admit. I could only think of three reasons for engaging in such behavior: to keep awake, purge his nostrils of boogers, or simply for pleasure.

Three drivers, three different personalities, all are good people who do a great job under difficult circumstances. I used to think that I’d like to be a driver for a NGO: you get to drive nice cars, you receive per diem when you’re out on mission, and there’s a certain status that drivers possess. But now, knowing that I might come under such close scrutiny, I think I might have to rethink my dream job.

Tuesday, September 13, 2005

The Drive to Diffa

This is going to be a tough clean up.

This is going to be a tough clean up.We left Zinder on Sunday mid morning and I felt I should have been more excited than what I was feeling. Up until Thursday, I’d never been east of Maradi and here I was about to travel to one of the last outposts in the farthest reaches of Niger near the Chad border, but too many long nights working in front of a computer screen had left me drained and edgy. The long hours had also left me somewhat of a mute; I felt I didn’t have enough accessible memory to run the language software in my brain with everything else going on inside. We were five, including the driver, and riding in the back seat sandwiched between Sanda and Moussa made me miss having my own personal chauffeur and Land Cruiser. Carpooling: just another sacrifice made in the name of the “Emergency.”

The road leaving from Zinder soon became a mosaic of asphalt and potholes. That I was even able to nap during the drive is either a testament to our driver’s ability or my overall fatigue, or perhaps both. During my waking moments I noticed less millet planted and more sorghum, and then, eventually, I stopped seeing anything planted, aside from Neem trees in the villages that bordered the road. Acacia trees could be seen farther from the road being visited by camels that used their height advantage and dexterous tongues to strip the young, tender leaves off the thorny branches. The colors out east, or at least those visible from the road, seem different to me than those in the west. My father wouldn’t find the red, red soil and rocks that imprinted so vividly in his memory during his trips to Niger. The soil (and the houses made from this same soil) look washed out, grey, and tired. It seemed to me pure folly that humans inhabit a place like this. But the human race has proven itself highly adaptable to even the harshest environments, and I would submit that Niger ranks in the top tier of the “Hardest Place to Live on the Planet” contest.

While seeming particularly hostile to humans, this part of Niger seemed perfectly suited for camels, goats and sheep. Seeing a goat perched up on its back tip toes trying to reach a tasty morsel that dangles temptingly just above its reach never fails to make me smile. Looking at the scene from afar you could easily think the goat is talking to the object of her desire, almost persuading it, from the oral gymnastics it’s going through to gain some purchase on said morsel. If goats ever figure out how to cooperate to make a goat-ladder, the Sahel is going to be in real trouble.

From the road, the pasture looked decent, but I was told that at this time of year the thickness and the color of the vegetation should be denser and more lush. And, during a pit stop I walked over to look at the grass and saw it was sharp-edged and filled with evil briars, not exactly prime grazing material. Still, the animals I saw looked surprisingly healthy. A few of the cows and horses looked more like skeletons, wearing their skin pulled tightly across their bones, but these were in the minority. Other than finding adequate forage from seemingly nothing, the other talent that sheep and goats posses, I’ve noticed, is sensing when to cross the road at exactly the right (or wrong) moment to make you stop or swerve to avoid hitting them. I’d like to think they do this on purpose, to have a good laugh with their buddies afterwards at our expense, but I don’t think so. All you have to do is look into the vacant eyes of sheep to know that they’re just not smart enough to pull something like that off.

At some point during the drive, sand dunes appeared. They weren’t the grand dunes that you might associate with the deep desert that go on and on, and disappear into the horizon, but were more low-slung and some were partially vegetated. But they’re on the move, no doubt, and they’re hungry. They have a particular appetite for the road and at certain points the sand had completely buried the asphalt. Not that this is an entirely bad thing in the right context. While we were stopped, so the others could pray, I took a moment to stretch my legs and I noticed a Peugeot station wagon, cum bush taxi, parked along side the road up ahead with its passengers sitting off to one side. I figured it had a flat tire or something and walked over to investigate. When I got to the car I saw that the bonnet had been completely removed and the entire engine compartment was filled with sand. The bits that weren’t covered in sand were charred black, visibly burned. The driver told me he didn’t have any water to put out the fire, but thankfully there was no shortage of sand.

Hadjia and Moussa spent a lot of the trip reading Koranic materials. Moussa, who made the pilgrimage to Mecca in 2003, was reading an Arabic/French dual translation of the Koran, with one page written in French and the other in Arabic. He had the French side covered with a piece of paper in an attempt to better his Arabic, but I could tell there was a lot of peeking going on. Hadjia seemed to prefer shorter pieces, all in Arabic, maybe the Islamic equivalent of the Upper Room. It wasn’t until we were about two-thirds of the way to Diffa that the significance of the date struck me: it was the fourth anniversary of 9/11. I didn’t think about the horrific details that took place four years ago as much as I thought about the perception of Muslims and their faith.

I wish more people could have the experience that I’ve had living in an Islamic society and alongside devout Muslims. Since being back, I’ve noticed how familiar the daily cadence, punctuated with the five daily prayer calls, feels to me. And I’ve slipped back into the habit of beseeching the will of Allah when I speak of things in the future that haven’t happened yet, and which might not happen—that’s only for Allah to know. The image of Islamic radicals who foment violence against others couldn’t be farther from my image I hold of people in Niger. Given the level of poverty and lack of education you might think these are volatile combinations that Islamic radicals would prey upon to recruit fellow zealots. But, by and large, it just doesn’t exist. I think most people would be shocked to learn just how tolerant Niger is of other religions. In fact, in the car ride I discussed with Moussa the unusual relationship that the Malagche have with their dead. I could tell he was somewhat shocked, especially the part about exhuming the remains of ancestors and fêting, but he didn’t pass any judgment. I don’t know what it is about Niger’s make up that produces such calm and tolerance, but it’s definitely a good thing and I wish there was more of it.

We finally rolled into Diffa around 6 o’clock. It reminded me a little of Konni in some ways—a little bit of a border town feel (Nigeria is only a dozen kilometers away and Chad is relatively close, I suppose), not many paved roads, and a kind of sprawling town layout. Noticeably different in Diffa, though, is the lack of the ubiquitous “cobble-cobble” drivers found in Konni: moped taxis, usually driven by teenage boys that queue along the road waiting for passengers.

We made the rounds at the office before retiring to CARE’s guest house. I made a quick tour of the facilities and in the kitchen, written on the wall, I saw, « 13/04/05 1ere pluie, 15h-16h». So little says so much: a promise and hope for another year, insha’allah.

Monday, September 12, 2005

From the Field

Here’s a picture I took en route to Tchintabaraden...only in Niger, huh?

I’ve been out in the field since last Saturday visiting the regional offices where CARE is distributing food rations to villages. At this time, CARE’s response to the food crisis is limited to the regions of Tahoua, Maradi, Zinder, and Diffa. In Tahoua, Maradi, and Diffa they are distributing food rations supplied by World Food Program and Niger’s government. In addition to the distribution, in Tahoua and Zinder CARE is opening feeding stations in select villages to aid moderately malnourished children. There are other NGOs who are also distributing food rations, but in terms of scale of operation and the number of people served, CARE’s operation is among the largest. They might have an advantage over other NGOs because they have been working in Niger for such a long time and already have a lot of resources on the ground and built up capacity in their staff. Also, being a large NGO with a worldwide presence, they can call upon experts from other field offices to help. I’ve met CARE employees and contractors on loan from CARE USA, CARE Germany, CARE France, and CARE Haiti.

So far, my primary role has been getting CARE’s field reporting operational. I’ve spent most of my time in front of a computer working with the various forms and reports that CARE is obligated to produce to satisfy the donors who are helping fund its operations, as well as to document and evaluate its actions during this period. Not very sexy, but I feel like I’m playing an important role. (Kristen wrote in an email that she was glad I’m doing important work; she would be pissed if I was just running the XEROX machine.) I have another week or so to go in this tour of field offices before I head back to Niamey. Once all the reporting tools are finalized, I’m looking forward to my secondary role: writing qualitative narratives, collected from the field, about the beneficiaries touched by CARE.

I've stolen some time to get this posted and now I have to relinquish the precious VSAT connection for some real work, so I'll sign off now. I'll try to post more soon.

Monday, August 29, 2005

Niger Bound

Yesterday, in Tana, I ran the Hash for the first time in Madagascar. It was the first event of the season, and there were a few other first-timers. Out of about 30 participants, only a handful of us ran the course, and I surprised myself by winning—something I never could have dreamed of doing in Niamey. There has been some talk of restarting a regional Hash in Fianar, and maybe that is something I could be a part of when I get back. There’s no shortage of possible routes around Fianar, that’s for sure. Last fall, back in Niger, I ran the Hash with Dave and some other friends, and at some point I ended up on the organizer’s email list. Since last January I have emailed this guy repeatedly asking him to take my name off his list. Then, before leaving Fianar, Kristen pointed out that now it’s good thing that I’m still on the list, since I’m going back to Niger.

Of course it was hard saying goodbye to Kristen Saturday morning. During the ten hours it took to travel the 400 kilometers from Fianar to Tana by bush taxi, I had ample opportunity to think about what I am doing and the consequences. When I wasn’t worrying about my immediate condition (the bush taxi, oncoming traffic, the nauseated woman puking into a bag seated next to me, etc.), I though about what leaving means to Kristen and me; to my integration into the Fianar community and the networking I had done for work. But mostly I thought about what my going to Niger might realistically accomplish. It’s a very far distance and not without expense, this trip, and I want to feel when it’s over that it was worth the expense, both emotionally and financially. Despite these small nagging doubts, I do remain excited and hopeful. In fact, on a personal/professional note, after feeling like Fianar and Madagascar have turned out not to hold kind of opportunities for me that we originally believed they would, this is just the thing I need to put a nice cap on my 2005.

So, tomorrow morning I’m off. I think some of my edginess will dull when I set foot in that familiar terminal, and my senses fill with the familiarity of West Africans (mostly) in various states of talking, sleeping, debating, and, above all, laughing. It’ll be homecoming of sorts, I suppose.

Check back in the coming weeks and months to see how things progress.

Thursday, August 25, 2005

Isalo National Park

Taking in the view at Isalo

One perk of Kristen’s fellowship is her time off. She has a standard vacation package, but in addition to this she gets all U.S. public holidays off, plus any Malagasy ones too. We recently used the Malagasy holiday of Assumption to plan a long weekend at Isalo (pronounced E-sha-lou) National Park. (Assumption is…anyone, anyone? The bodily taking up into heaven of the Virgin Mary. Yeah, who knew?)

Based on geology alone, you could easily think you were in parts of Nevada, South Dakota, Arizona, and Utah. But, throw in the tropical vegetation and otherworldly lemurs and you cannot help but feel awed by what the unusual and wonderful confluence of geology, botany, and evolution has produced in Isalo. As clichéd as it sounds, you feel like there is no other place on Earth quite like this.

We left Fianar on a Friday morning and drove four hours south to Ranohira, the gateway to Isalo. The freshly paved road and gorgeous scenery of granite slabs and mountain ranges truly made the drive a pleasure. Ranohira is a proper town, with a filling station, shops, restaurants, and hotels, and now seems to be in the process of developing its ecotourism market.

Our plan was to spend one night in Ranohira and two out in the park camping. The Park office, located in town, is where you pay the park entrance fee and arrange a guide for your visit. In a departure from our normal hiking and camping practice, we hired two porters to carry our packs to and from the campground. We arrived at the Park office Friday afternoon, after finding a place to sleep for the night, and it was hopping with other tourists. Friends had warned us to properly vet any potential guides using the «Livre d’Or », a registry used by visitors to rate their guides. After hearing stories of guides tossing their cigarette butts on the side of the trail, making uninvited passes at women, and refusing to honor the agreed upon itinerary, we wanted a good guide.

We were also warned that during the tourist high season, finding a good guide to go out in park overnight with one client would be tough. During this busy time, a lot of visitors are interested only in taking day trips to see the sights easily accessible by car. Guides know this and avoid making overnight trips, preferring instead to take as many day trips as they can, with as many clients as they can, to maximize their earning potential. This proved to be the case with us. Upon arriving at the Park office, guides besieged us and offered to take us into Isalo. Then, after learning we wanted to spend two nights out camping, nobody seemed available to go out with us. It was frustrating and at one point I walked out of the office to check on the truck and cool down. While I was at the truck a young guy approached me and offered to be our guide. He introduced himself, Dolphin, and explained he was a guide-in-training with two years experience and wouldn’t mind going out for two nights. Not having many other options, we vetted him against the registry and agreed to go with him. He arranged to find two porters and we agreed to meet at the Park office early Saturday morning to get an early start.

With the details of the park visit hammered out, Kristen and I struck off to explore some of the sights around Ranohira. We took in a nice exhibit at a nearby museum and then wandered out to La Fenêtre, a rock formation with a cutout in the middle, where visitors can go for a spectacular sunset. Arriving a bit early to witness the sunset, we took in the scenery, which was very picturesque in late hours of the afternoon. Some rocks sported strikingly green lichen that contrasted nicely against the orange hues in the rock. After La Fenêtre, we wandered out to a posh hotel to watch the sun go down. «Le Relais de la Reine » is an up-market, French-owned hotel built harmoniously into the landscape. The choice of building materials, colors, and layout reflect the extreme level of detail that has gone into the hotel. (Just for comparison, check out where Kristen and I spent Friday night after our drink.) We sat on an outdoor landing and enjoyed a drink as the setting sun reflected off nearby canyon walls.

Saturday morning came quickly and we waited for Dolphin at the Park office. He showed up late; we learned afterwards that his watch would not keep the time, something we all laughed about throughout the trip. We watched the porters walk off to the market, wearing our packs, to buy their food for the two days, and then Dolphin, Kristen and I headed off to the park.

During our two days we saw about as much of the park as is possible without a 4×4 vehicle. We walked across fields, through canyons, over mountains, and down crevasses; swam in natural pools, in water that was unbelievably clear (and cold); spotted all kinds of birds and three kinds of lemurs, including a little baby lemur still clinging to and breastfeeding from its mother; marveled at miniature flowering baobab trees that could have been over 1000 years old; and drank in the expansive landscapes like thirsty travelers. Living up on the plateau and around the corridor has made us a tad claustrophobic and eager to spend time in the wide open country.

We camped both nights at an established campsite that had running water and a proper toilet. Both nights the camp was completely full. Apparently tour group operators bring their clients to the camp for a real “backcountry” experience. It’s a pretty slick operation, complete with guides, porters, and cooks. Both nights after dinner when the clients had been fed and were sated, the tour staff broke out guitars and drums and worked through a long set of Malagasy classics. In our tent, a stone’s throw away, we enjoyed the music the first night, but the second night the band played until 11:30pm and kept Kristen awake.

Monday morning we broke camp, packed up and watched as our backpacks, again strapped on to the porters, disappeared ahead of us towards Ranohira. We walked slowly, groups of incoming visitors and their guides passed us on the narrow trail, and we settled back slowly into the reality that we were going back to Fianar and that the next day Kristen would be leaving bright and early for a trip into the field.

Back at Ranohira we saw our packs leaning against the outside of the Park office. We settled our bill with Dolphin and the two porters, and Kristen made sure to add our review to the registry. As we drove back to Fianar we schemed up more ways to take advantage of Kristen’s days off.

Friday, August 19, 2005

The Accidental Dignitary

Presidential Ride

About a month ago we were up in Tana for about a week taking care of some business, and on Friday, when the week was over, we decided to break up the return to Fianar by spending one night in Antsirabe. Antsirabe is about a two hour drive south of Tana and the city has a charming feel, thanks to its interesting architecture and wide boulevards. We stayed the night at a cute bed-and-breakfast and had the place to ourselves. We enjoyed a walk about town, a nice dinner, and a bit of shopping during our stay. A few key Malagasy phrases kept the persistent pousse-pousse (rickshaw) drivers at bay; unfortunately, the beggars proved more insistent. Then, after a leisurely walk Saturday morning, we loaded the truck and headed south to Fianar. During the drive, traffic was light, the weather clear, and the going easy.

This last part came to an abrupt end around noon, when we arrived at the bridge leading to Fatihita, a small town north of Ambositra. About a kilometer before reaching the bridge we noticed lots of cars stopped and pulled off on either side of the road. Not realizing what was going on, and not thinking, I simply drove on past the parked cars until I saw soldiers blocking access to the old bridge, at which time I pulled behind an army truck to park. During the Crisis of 2002, supporters of Ratsiraka, the former president, blew up the bridge in an attempt—that worked—to halt the flow of goods and people to the capital, Tana. When Ravalamanana, and his party, assumed power after the Crisis, the government built a temporary one-lane bridge over the collapsed one, and construction on a new bridge, financed by the EU, began. Construction on the new bridge wrapped up recently, but for as long as we’ve been here, traffic was still made to use the old one. And, on the way up to Tana we noticed that a big grandstand, decorated with Malagasy flags, had been set up for what appeared to be a ribbon-cutting ceremony. Now, on the way back down to Fianar, we discovered that we were arriving just in time to witness the grand opening of the new bridge.

After stopping, Kristen quickly hopped down from the truck and joined a crowd of people who had gathered by the old bridge. Soon afterwards, an official caravan of dignitaries began to cross the old bridge from the other side of the ravine towards us, en route to the grandstand. About 50 meters from the end of the bridge a midnight-blue Land Cruiser sporting diplomatic flags and dark-tinted glass (and probably bullet-proof, too) stopped and out stepped the Malagasy President, Marc Ravalamanana. At the bridge, someone in the crowd next to Kristen said in a surprised voice, “That’s Ravalamanana!” Kristen, who was only some twenty feet away, told me later that the President looked young and full of energy.

Behind the President came a flock of guards and other diplomats, including a heavy-set, big-jowled man who we concluded must be the head of the EU for Madagascar. The procession made its way to the grandstand and we then spent the next three hours waiting for the official ceremony to end, so we could continue our return home.

There were literally thousands of people in attendance at the bridge opening ceremony. We could see across the bridge to the other side and people spilled down from the hillside. Food vendors circulated among the parked cars and crowds of people selling fried chicken and fish, steamed crawfish, boiled cassava, oranges and bananas. In addition to all the spectators were many soldiers and police. In fact, security around the President was pretty high and included bodyguards dressed in suits, as well as armed guards around the grandstand and sharpshooters on the hillside above the grandstand.

On the whole, it was all pretty spectacular. After three hours, and what seemed like an eternity of listening to Malagasy speeches, the official opening ended and the big-wigs made their grand exit by taking leave in three helicopters. The less important officials, traveling by more modest means, queued up in their vehicles along the old bridge. Unknowingly, when I ignored the other parked cars and continued right up to the old bridge, I secured pole position among the other parked cars and bush taxis, which had by now jockeyed for position in every open space of asphalt and were tightly packed together back as far as the eye could see. The logjam of cars prevented the official entourage waiting on the old bridge from moving, so soldiers began barking orders at the parked cars to make enough room for the cars to pass by.

In the confusion that ensued, we somehow got mixed into the official caravan going south over the new bridge. A soldier looked at our white truck (and maybe our white skin) and green plates and just waved us into the pack of other white official vehicles. Only happy to comply, I turned on the hazards and fell into line with the other cars as we were among the first cars over the new bridge. After we passed the grandstand, we slowed to maneuver through the “cocktail” party going on along the road after the bridge. We, the official caravan, crawled along at a snail’s pace for the first couple of kilometers while we waited for soldiers to clear parked cars from the road shoulder to free up traffic. Finally, we hit open road and we waved to the other white vehicles as they passed us, one by one, and sped off to their final destinations.

The bridge delay cost us a daytime arrival to Fianar, but nevertheless we were in good spirits: we had a close brush with the President, saw three helicopters take off and drove with the official caravan over the brand new bridge. However, maybe more exciting to us was deciding what to do with the huge bucket of strawberries we had bought in Tana.

Wednesday, August 17, 2005

Home Sweet Home

Kristen and I have finally settled into our apartment and we thought we should post some pictures of the place. Locate the white truck poking out of the garage and then count the next two arches to the right, these three arches are all part of our apartment (plus the upstairs portions, of course). The building was originally built as part of a vineyard operation, but now has been partitioned and converted into seven apartments. The layout is very nice. There is an inner courtyard with a patch of grass that will eventually be landscaped with flowers and trees. It also has a very strange fountain, but we aren’t complaining because we are hoping it provides some white noise against the barking dogs at night. A clothes-drying area is being constructed atop two garages, which will be nice when it is finished. (The shot above was taken from here.)

Our neighbors, the Fruendenbergers, are also American and Mark is Kristen’s mentor for her fellowship. They moved into their place a couple of years ago after their other apartment was destroyed by fire during the 2002 Crisis. Until we moved in, they were the only residents in the entire complex, which is probably because theirs was the only place completely renovated. Our place was mostly finished when we moved into it mid May, but it has taken until now to get all the little details hammered out. Now that it’s done, we’re very happy and feel well settled. Check out the blueprint to get a sense of the layout.

The other units are in the last stages of completion, although this doesn’t mean they’ll be habitable before Christmas. Construction around here is maddeningly inefficient and illogical at times. It’s not unusual for a wall to be put up, cemented and painted, only to later see it chiseled apart to make way for the electricity or plumbing. Take two steps forward, one step back. The landlord has been busy showing the units, but he’s been having a hard time filling them. We did hear news that a Malagasy family is moving into a nice three bedroom unit soon, but we’ll see if that turns out to be a truth or fiction.

Saturday, August 06, 2005

School Days

Here’s a class picture from my month-long intensive French language course. The local chapter of the Alliance Franco-Malgache puts on language courses periodically and this is the second one I’ve taken since being in Fianar. We covered a range of topics, most dealing with some aspect of French language and culture, and I was often called upon to provide the American perspective. As the photo reveals, a few nuns took the class, and frequently they provided the class with much unintended hilarity. One day, after working on personal presentations to make to the class, a nun put the class in stitches when she declared the obvious: she was single, and a practicing Catholic.

Sunday, July 31, 2005

Skype

Since living in Madagascar, we’ve experimented a bit using Skype, a kind of Internet telephone, to talk with Kristen’s family. I don’t really have the technical expertise to explain how Skype works aside from saying that you use your computer, the Skype software, the internet, and a microphone to talk to other people. To get a more technical explanation you can check out the review from PC Magazine. The best thing about Skype is that it’s FREE! We had some initial kinks, but our last conversation was clear and the lag was hardly noticeable. Email and the blog are good for keeping in touch, but now we want to use Skype to talk with more of you. If you’re interested in joining the conversation, here are the steps you need to take to get up and running on Skype.

- Consider your connection speed. We tried using Skype from home with our dialup connection and found the reception not good. However, with us using Kristen’s office connection and Rob on cable modem, the reception was great. So, we’d say Skype is not recommended for dialup users.

- Download and install the software on your computer. Point your web browser to www.skype.com/ and follow the links to the download page. The file is about 6MB in size.

- To get the best results and reception you really need a headset with a microphone. Before leaving for Madagascar we stopped by Best Buy and bought a set from Logitech for about $25. The headset has two jacks: one for the microphone and the other for the headset. You really need the microphone close to your mouth while speaking in order to have the clearest reception; however, you can choose to not plug in the headphones and use your computer’s speakers instead to listen to the conversation.

- Once the software has been installed, choose a username.

- Then you can search for contacts (easily done from the Getting Started Wizard dialog box under “Search for Other Skype Users”). You can enter in our username, kppandedp, and you should find us and then be able to add us to your contact list.

- Set up a time to Skype via email. Since we need to plan to be at Kristen’s office, it’s usually better to give some advanced warning. And, we’ve found it’s usually best to arrange something during the weekend, since the office is mostly empty then. (FYI, the time difference to Madagascar right now from the East Coast US is 7 hours.) Be sure, in the email, to let us know your username so we can add you to our contact list too.

It’s that simple, try it. Hope to be talking to some of you soon!

Thursday, July 28, 2005

FOOD CRISIS IN NIGER!

Hungry children in Niger

There is a food crisis Niger, the country where we served as Peace Corps volunteers. Niger was our home for over two years, and is still home to many people who we cherish deeply. Family members and friends who came to visit us in Niger can attest to the astounding and humbling generosity of Nigeriens. In a country so poor, people share so much. Our friends in Niger taught us what it truly means to give, and to receive. We feel compelled to ask you to consider donating to help the people of Niger. Our individual donations might seem small, but together they can and will save lives.

Niger is the second poorest country in the world. Even in a good year, a sizeable proportion of the population is malnourished. This year has heralded in the worst famine in Niger since 1984. People our age remember the song “We are the World” from elementary school, written to raise money for the famine of 1984, which encompassed much of the Sahel. Of Niger’s 13 million people, nearly one-third are on the brink of starvation: 800,000 of them are children. The lack of rain and locust invasion in 2004 is primarily to blame for this condition; however, Niger is perennially in a state of food insecurity. That there is a crisis this year isn’t surprising. We were working in Niger last fall and in late August, we witnessed the second rain of the season in Tahoua (in north central Niger); the rainy season usually commences in late May. We also heard reports from current Peace Corps volunteers, particularly those living east near the city of Zinder, that in their region the millet grew knee-high, and then stopped, never producing any grain.To read, see, and hear more about the crisis in Niger, follow the BBC’s recent report on the subject. Friends of Niger, an organization that we are members of, also has information about the crisis.

Until last week, the response from the international community had been abysmal and inadequate. U.N. Emergency Relief Coordinator Jan Egeland said on CNN earlier this week that had the international community responded to Niger’s food crisis when asked, the cost of treating one hungry child would be approximately one dollar; today the cost is 80 dollars. In the past couple of days, some relief activity has finally commenced, but more help is needed. From our experience as volunteers, the “hunger season” between July and October is particularly difficult for Nigeriens. This year it is disastrous. By now fields have been planted, labor demands are high, and food stores from the previous year have likely begun to run out (for those who got a harvest last year), and all farmers can do is watch the skies for rain clouds to come. Assuming that the rains are decent during the growing season, people will be able to harvest their millet, beans, and peanuts in September or October. This is why the timing of relief now is so critical.Please consider helping further relief efforts in Niger. Time is of the essence. We know that making a choice to donate is a difficult one, especially deciding whether to support the acute problem of today versus the problem of food security in the long term. Also, choosing an organization isn’t always straightforward: Do you choose one that earmarks donations for Niger specifically, or do you support an organization generally and hope that the funds go towards programming that will ultimately help countries like Niger? Personally, we are going to divide our donation between a development organization and a relief one. These aren’t easy questions to answer and we can only suggest that you do what feels right to you.

For those of you who wish to earmark funds specifically for Niger, we can suggest making a donation to one of the following:Save the Children

Feeding stations for children facing starvation in Niger are staffed by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF). To make a general donation to this organization, please follow this link.

To help support general development programs in Niger, in order to help the country become more food secure in the long run, we suggest supporting the following Non-Government-Organizations. We got to know the country directors of CARE and CRS when we were in Niger last fall, and trust that they are doing good work.

For those of you living in or near the San Francisco Bay Area, Tiffany Martindale (RPCV Niger ‘98-’02) and Josh Schnabel (RPCV Niger ‘00-’02) are selling bumper stickers at $7.00 a piece that read Kala Suuru and Sai Hankuri (“Have Patience” in Zarma and Hausa, respectively). For a bumper sticker, please contact Tiffany: maycinga@yahoo.com.And finally, please consider calling, writing, and emailing your elected representatives in Washington, DC to implore them to immediately increase the U.S. contributions of humanitarian and food aid to Niger.

Contact information for your US Senator or your US Representative.Thank you for helping. Much love, Kristen and Dan

Friday, July 15, 2005

Weekend at Park Ranomafana

Hiking in the forest

We spent last weekend hiking in Parc National de Ranomafana, about 60km north of Fianar. Kristen had been out in the field since Wednesday visiting communities around the park where SantéNet is working. When her plans called for her to spend Friday night, and then Monday and Tuesday in Ranomafana, it made more sense for me to come out and spend the weekend with her in Ranomafana than for her to come back into Fianar, only to turn around and go right back two days later.

The road leading to the park is, by Madagascar standards, pretty good. However, with that said, back in April we took this route to attend a conference on wild silk production, held just outside the park, and on the way back to Fianar I had to move up to the front of the mini-bus to avoid upchucking. Potholes and S-curves truly make for some exquisite motion sickness, and I now understand why many Malagasy travelers do a dose of Dramamine before starting any long journey by car. I found driving better than riding: a top speed of 15mph helps.

Bad for setting land-speed records, the slow speed, however, was perfect for taking in the scenery. At one point, there was park property on the left and non-park land to the right, juxtaposing two very different possibilities/realities. I saw people felling and milling eucalyptus trees to my right. To accomplish the latter, the foresters lay the felled tree upon make-shift scaffolding, and then, with one person standing above and another below, they carve planks from the bole with a 6-foot long saw. As I continued the drive I saw more tell-tale piles of amber sawdust dotting the hills and valleys and wondered how many board-feet of lumber comes out of this area in a year. The other side of the road, by contrast, was a dense mat of vegetation—a mixture of trees, ferns, and other greenery—that looked impossible to walk through. Considering Park Ranomafana is only about 10 years old, it looks like the conservation efforts put in place have had some benefit.

Not to be misleading, though, the park itself is far from pristine, as we found out during our hikes. There are still exotic, introduced species in the forest composition, with wild guava being one of the most aggressive. Lemurs and birds that eat the guava fruit and later disperse seeds via their feces hinder eradication efforts of this species, our guides told us. We also encountered zebu cow-pies in the forest (but none of their authors). Some livestock owners leave their cows in the park to their own devices, and only seek their animals when they need to sell or sacrifice one. And, even when we walked in the primary, old-growth forest, we found an occasional cut tree stump indicating the presence of some recent human activity.

In Malagasy, Ranomafana means “hot water.” The hot springs that surround this area are the inspiration for the name. There are baths and a heated swimming pool in town with a two-tiered pricing scheme for locals and strangers. We had read in the guide books that the facilities, on a hygienic level, were not up to code, so we opted not to bathe there. Others, who didn’t share our same standards of cleanliness, took advantage of a warm bath or swim to help ward off the winter chill. The only ranomafana we encountered came from the shower in our bungalow, which was a welcome blessing after our cold and rainy hikes.

Calm before the storm

We hiked both Saturday and Sunday, with Erica, a third-year Peace Corps volunteer who has extended to work with SantéNet in Fianar. Saturday, we signed up for an afternoon and nocturnal hike, the total time out to be around 5 hours. That afternoon we hiked mostly in the secondary forest, which was full of trees, bamboo, ferns, and orchids. We also visited a small waterfall that was booming with water. It began raining about an hour into our hike and very soon we were pushing the limits of our Gore-Tex outerwear.

We didn’t see much wildlife, unless you count the leeches, which found us quite appetizing. Even with our pant-legs tucked into our socks, the leeches managed to infiltrate our defenses. Erica suffered the worst, her ankle-length socks provided little defense against the persistent suckers. However, Kristen won the prize for most prominent leech attachment: her face. The leeches are more a psychological menace than a physical one, although if they are disturbed or forcibly removed after attaching, they secrete an anticoagulant that makes the wound site bleed spectacularly. (Note: Hi, this is Kristen, sneaking into Dan's story. I'd just like to state for the record--especially if my Mom is reading this--that as soon as Dan saw the leech on my cheek, I wanted it off. However, Dan and Erica insisted that if 'we' just left it on for a few moments until it was done feeding, then it would be easy to pluck it off and my cheek wouldn't bleed one bit. The few moments seemed to stretch on forever, and while everyone else was watching the mouse lemurs, I had to keep prodding them to check my face with the flashlight to see if the leech was 'done' yet. My calmness ran out as the time moved towards 10 minutes and I made Erica remove the leech. Judging by all of Erica and Dan's chuckles, the experience was more fun for the observers. Luckily there is no trace on my cheek of my temporary 'friend')

For the nocturnal hike, our guide told us to bring bananas and meat to lure mouse lemurs and civets to a designated feeding spot. We had reservations about engaging in this questionable practice, but ultimately decided to go along with it since these animals are only active during night and usually reclusive. And, sure enough, upon arriving at the designated spot, we found a clearly habituated civet waiting for a morsel of meat. Eventually another showed up to make a pair, but they were to be disappointed this night because we drew the line at hiking with raw meat in our packs. The guide took our bananas, peeled a couple to rub on some trees, and stuck some others on nearby branches. Soon afterwards we saw movements in the shadows and our flashlights revealed a mouse lemur, the world’s smallest primate. It was cute, and the way it flitted about the branches reminded us more of a bird than a mammal. We took pictures and were glad to have seen these animals, but decided ultimately that the whole experience was a bit sad and disturbing. The civets just looked sad and cold and the lemur appeared jumpy and strung-out. Maybe being so close to the civets--who find mouse lemurs tasty--explains the mouse lemur's erratic behavior.

World's smallest primate

Sunday, we hiked in the morning—again in the pouring rain—but this time up into the primary forest. On the way up, we saw a chameleon, a Grey Gentle Lemur, high up in a patch of bamboo plants, but not much else except, of course, more leeches. Kristen had fun playing in the streams and spent some time reliving her childhood looking for crayfish. She flipped over one rock and found a fresh water crab, about the size of a quarter. The highlight for me was seeing so many orchids in their natural setting. Our guide told us the time to see the most orchids in bloom isn’t until the warmer months of November and December, but we did see a miniature species proudly sporting its pink blossoms. I look forward to going back just to hunt for orchids, which me might do Thanksgiving weekend.

Wednesday, June 22, 2005

Update and musings from Fianar...

Kristen is off attending a conference on Population and Health in